Link to SS Governor history and underwater images:

http://www.scret.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=33

Multibeam imagery of the ship included below:

Link to SS Governor history and underwater images:

http://www.scret.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=33

Multibeam imagery of the ship included below:

Excerpt from Baldt Anchor & Chain; included here as evidence the Chatham may have carried cast malleable chains for use with its stream anchor.† HMS Chatham was only 80 feet long, but nearly 140 tons which is to say she was damn heavy.† The use of chain presents itself as appropriate for a ship this weight.

[From the time of Caesar until the the 13th Century we find little or no mention of the use of anchor chains. Between 1200 and 1700 A.D. we read that iron cables are sometimes used. The statutes of Genoa of 1444 make brief mention of “iron anchor chains.” An engraving of 1512 shows a ship with hawse holes and anchor chains clearly depicted.

Again a lapse until in 1634 Philip White patented in England “A WAY FOR THE MEANING OF SHIPS WITH IYRON FOR THAT PURPOSE AND THAT EH HATH NOW ATTAYNED TO THE TRUE USE OF THE SAID CHAYNES AND THAT THE SAME WILBE FOR THE GREAT SAVEING OF CORDAGE AND SAFETY OF SHIPPES AND WILL REDOUND TO THE GOOD OF OUR COMMON WEALTH.”

In the ensuring half century a few far sighted ship owners and ship captains had sufficient faith to experiment with iron chain, for in 1771 the French explorer Brouganville complained that he had lost six anchors in nine days and narrowly escaped shipwreck, which would not have happened had his ship been fitted with iron chains.

In 1778, General George Washington conceived the idea of a buoyed barrier chain across the Hudson River, at West Point, N.Y. as a means of impeding the invading British fleet. In six weeks seventeen American blacksmiths forged a 1700 ft. long chain of 3-1/2 inch square stock weighing 275 pounds per link. This chain is still preserved at the US Military Academy, West Point. N.Y.

In 1783 George Matthews, of England, 150 years ahead of his time made cast malleable chains for ships. It was not until World War I that cast steel chains were fully developed.]

Source: Baldt Anchor & Chain (Chester, PA)

Repost of Content Compiled by Underwater Admiralty Sciences:

Original Content Located Here: http://www.nwrain.com/~newtsuit/uas/vancouver.html

Chatham’s Anchor:

It is always a matter of chaos and immediate action when a vessel loses its anchor. It borders on catastrophic when the vessel is thousands of miles from its homeport and is carrying no spare. This unwelcome circumstance assailed the Chatham, one of the two vessels of the Vancouver expeditions in the cold and deep waters off the San Juan Islands. That anchor, lost two hundred and ten years ago, almost certainly lies now where it was lost. Additionally it is the only empirical proof of Vancouver’s exploration and British claims in the Northwest.

To explain the circumstances for the loss of the anchor we begin with the departure of the HMS Chatham in England…

As loved one’s waved goodbyes and government officials eagerly encouraged the departure to grab lands in the New World, the Chatham left England on April 1st, 1791, as the Armed Tender to the HMS Discovery, the flagship of Captain George Vancouver. Both vessels were bound for the Northwest coast of America. In April 17, 1792 they reached soundings off the Cape of Mendocino in Northern California. Traveling north they would venture in close (but not too close as too close was often an invitation to disaster) to shore to explore, sound, map and observe the local fauna and topography. At night they would stand out to sea for safety. Safety from the tides, reefs, rocks and unfriendly locals. On April 29th they entered the Straits of Juan de Fuca. A few days later, at the suggestion of Lt. William Broughton, commanding officer of the Chatham, they anchored in a very large bay. Calm waters and an abundance of fresh water and game beckoned them to the first anchorage for the expedition and was named Port Discovery after the expedition’s flagship. It was later changed to Discovery Bay.

According to logs, for the next two weeks, Vancouver used this calm bay as a base from which he and his men, in open boats, explored the upper waters of what is now Admiralty Inlet as well as the total waterway of Hood Canal.

On May 18th Vancouver personally explored the large hill on Protection Island, which sits astride of the opening to Discovery Bay. From the summit of Protection Island one could see many islands – the San Juan Islands – to the northeast. Vancouver directed Lieutenant William Broughton, the commanding officer of the Chatham, to explore those islands while he and the Discovery explored the waters to the south.

Broughton set out on that reconnaissance on May 18th, 1792. He returned to the Discovery anchorage between Blake and Bainbridge Island on May 25th, 1792Vancouver made in his journal one brief entry mentioning Broughton’s exploration:

“Mr. Broughton informed me, that the part of the coast he has been directed to explore, consisted of an archipelago of islands lying before an extensive arm of a sea stretching in a variety of branches between the N.W. north, and N.N.E.”

Vancouver’s sparse entry leads one to believe that Lt. Broughton had accomplished little during his week of exploration. Fortunately, however, Lt. Broughton’s hand-written report of his exploration of those islands, (known today as the San Juan’s) is preserve and now located in the British Nautical Museum. The report reveals that the men of the Chatham were far from idle.

The existence of Lt. Broughton’s manuscripts has long been known. It was one reprinted by the Washington Historical Quarterly under the title; “Broughton’s log of a Reconnaissance of the San Juan Islands 1792.”

The British Hydrographic Office – in England – archives materials from the Vancouver expedition. Of particular interest is a hand-drawn chart by Lt. Broughton with only two places named, “Birch bay” and another Bay.” The first glance at the chart is puzzling; its features look completely unfamiliar. But, when you lay the hand drawn chart next to a modern navigational chart of the American San Juan Islands the similarity is immediate. Only a handful of the rough charts of the Vancouver expedition have survived to the present day. It was argued that without a doubt, the chart of Lt. Broughton was the first chart of the San Juan Islands, however scholars since have noted that Francisco Eliza and crew, aboard the San Carlos, a Spanish Brig, did the “first chart” of the San Juan’s the year before in 1791. Juan Carrasco was the mapmaker.

With the chart, and in conjunction with Broughton’s written accounts, one can easily reconstruct the course of the Chatham as it maneuvered through the tricky and unknown current and waterways of the San Juan Islands. After leaving Discovery Bay, the Chatham sailed almost North across the Straits of Juan de Fuca. On that passage Broughton observed the opening between San Juan and Lopez Islands and set his course for the southern gateway into the islands. Sending a small boat ahead to sound the waters of that turbulent and threatening passage, Broughton proceed with caution through Cattle Pass and into the broad expanse of water between San Juan and Lopez Islands. Using a dash line to mark his progress (as on the original handwritten chart of Broughton) the Chatham passed through Cattle Pass at the lower left side. Late that day Broughton sailed the Chatham in the Upright Channel between Shaw and Lopez Islands, anchoring at night off of Lopez Island.

The next day Broughton sent out two long boats under the command of James Johnstone, master of the Chatham, to explore the northern area Johnstone charted what we now know today as Waldron, Skipjack, Spieden, Johns and South Pender Islands.

The next day the tireless Johnstone returned in the Chatham’s cutter to Cattle Pass to sketch the entrance through which the two vessels had passed between Lopez and San Juan islands. At the same time there was no wind, so Lt Broughton ordered that the two long boats tow the Chatham toward the opening between Orcas and Blakely Islands.

On the 21st the Chatham worked her way through Peavine Pass into Rosario Straits and on the following day Broughton sailed the Chatham across Rosario Straits to a protected cove.

All during this time the Chatham was among the islands, Lt. Broughton had been sending out exploring in all directions. By the 23rd of May 1792 he felt he had carried out his mission for on that date he sailed southward to rejoin Vancouver and continue the explorations of the water south of the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

After completing their explorations south making it as far as Commencement Bay in Tacoma, both ships headed north for the safety. The southern portion of Puget Sound was susceptible to SSE storms with abundance of severe currents and tides. It was during the northbound trip when the Chatham suffered the loss of her stream anchor.

The wind had failed and as the Chatham was crossing an unknown channel when, she was caught by the flood tide and swept helpless, to the northeastward. To slow her progress in the waters of unknown depth the stream anchor was dropped. When the vessel was brought to, the strain was too much and the cable parted. Moments later the Chatham let go of her bower and the vessel was stopped before potential disaster occurred.

This was a serious moment the potential for disaster was noted in the journal entry by Edward Bell, the young clerk of the Chatham:

“We found the tide here extremely rapid and endeavoring to get around a point to a bay in which the Discovery had anchor’d, we were swept to leeward of it with great impetuosity. We therefore let go the Stream anchor, but in bringing up, such was the force of the tide that we parted the cable. We immediately let go with the Bower with which we brought up. On trying the tide we found it to be running at a rate of 5 Ĺ miles an hour. At slack water we swept for the other anchor but could not get it, after several fruitless attempts to get it we were at last obliged to leave it and join the Discovery.”

And Archibald Menzies, the naturalist of the expedition, made the following journal entry:

” — the Discovery with the assistance of her boats was able to get into the East side of the opening near the entrance where she came to an anchor at 6:00 in the evening, while the Chatham was impelled by strong flood tides into an opening a little more to the eastward, in which situation as neither helm nor canvass has any power over her, all were alarmed for her safety and anxious to hear of her fate.”

On the following day Menzies journal stated:

“Next day a Boat came to us from the Chatham when we were informed that she was at an anchor in a critical situation at the entrance of an opening eastwards of us where they lost their stream anchor by the force and rapidity of the tide which ran at a rate of about five miles an hour and snapped the cable as they were bringing up, as often as the tide slackened they used their endeavors by every scheme they could think of to recover the lost anchor, but without success and the loss of it was more severely felt as is was the only one of the kind they has been supplied with.”

| The ship carried other more laborious anchors but quite often the stream anchor was the anchor of choice after a long day in unknown waters – such luxury would be sorely missed.

It is regretful that better land references were not made of the lost anchor’s position but at the moment the critical nature and safety of the Chatham took priority. I am sure that none of the officers or crew would have ever imagined that 210 years later individuals would be reviewing their journals in an effort to locate the lost anchor. The events and journals are the proof that Vancouver’s expedition vessel Chatham lost an anchor. Charts today can be examined and with relative ease the above information and actions can be tracked. The information recorded in the journals give us critical clues as to the location of the lost anchor. Today technology, specifically a “Proton magnetometer”, can locate this anchor given the mass and the nature of the ferrous metal, in any bottom composition. Facts indicate – after trips to the site – that the bottom is rocky. More likely than not, the anchor became lodged in rocks and when tensions was taken up by the Chatham’s movement in the current the mass of the ship proved to be too much for the wedged anchor and cable to hold. The cable parted and the anchor remains on the bottom. The renowned shipwreck archaeologist Jim Delgato estimates the anchor’s size somewhere between 6 to 9 feet in length – a square shank and weighing around 700 to 900 pounds. The fluke tip to tip is approximately 3 feet and the stock was made of English Oak, most likely, the marine wood boring organisms has consumed the stock. For [218] years the only known artifact to have been left by Vancouver’s expedition is the lost Chatham Anchor. Its location and recovery will stir international interest and a legal battle over ownership. In the end, the Anchor will be preserved and be a modern reminder that we can capture moments from the past and allow them to be enjoyed by all. |

I heard from the president of an Amphibious Attack Boat Group ‚Äď a group of guys who use to be LCVP operators in WWII.

I wrote them some time ago about the LCVP we found in the lake, and asked if they had any info on it. I communicated that our LCVP was identified as PA 52-22.

They indicate the PA52 designation means the LCVP we have was once a part of a ship named Sumter. In doing further research the Sumter carried 36 landing craft all of the PA 52 designation. Ours was Landing Craft # 22 on that ship.

In the last three weeks we’ve had a number of dive teams on the YMS doing initial exploration. The wreck has now been penetrated in a number of areas, but so far no designation numbers or other identifying marks have been found.

The primary points of entry have been in two areas: the pilot house and the main cabin below the pilot house – with both areas offering further pentration opportunity once inside.

In the case of the pilot house, there is a small room aft that appears to have been used as sleeping quarters. The space is very tight, with various debris making exploration difficult.

In the case of the main cabin, there is an additional door forward which has not yet been breached, and a small opening with ladder that leads staight down into the belly of the ship. This lower deck beneath the main cabin has now been explored, both forward and aft. We had hoped that there would be a path that lead from these rooms below the main cabin back to the engine room, with an exit opportunity through the hole in the stern deck where the engines were removed. Unfortunatley this is not the case. The path forward leads to a deadend as would be expected this close to the bow, and the path backward appears to lead to a solid wall – possibly a firewall separating the engine room from lower sleeping quarters.

The lake visibility has been particularly bad the last three weeks, but the interior visibility of this wreck has been completely horrible. We have divers talking of not being able to see their own 18W HID lights, rust and other particle matter continously falling from the ceiling, errant wires hanging about, it is just generally a nightmare in there. 100% of those that have entered the room below the main cabin have exited via touch contact with the cave line they established on the way in. Very dangerous.

JaWS Diver Scott Boyd (www.boydski.com), who is known for taking some of the best underwater wreck photos ever captured in Lake Washington, was on the wreck this past Sunday as my dive partner, but we’re all going to have to wait until the visibility clears up before we get to see any of his photos.

I include a photo below to show established & expected penetration paths. ‘X’ marks a known deadend and ‘?’ marks paths yet to be explorted.

We put two teams of divers on the ‘new’ YMS the last day of 2007. It is a fantastic wreck; truly one of the best in the lake.

We spent 25 minutes at depth and left feeling like there was a significant amount left of the wreck to explore. As mentioned before the engines, weapons, pilot house controls and various brass components look to have been removed prior to sinking, but otherwise this wreck is intact. Plus there is a signifanct amount of debris throughout.

The Pilot House still holds a knocked over filing cabinet, the bathroom is complete with head and cabinetry and there are various other artifacts inside cabin rooms, on the stern deck – including two large generators, and on the bow.

One thing we have not yet found is any designation numbers indicating which YMS we might have. Determining whether numbers can be located will be the focus of future dives.

Some images, taken from video shot by SCRET diver WJ, included below (click to enlarge):

More reports on this one to follow. We’ll dive it fairly actively over the next few months.

JaWS

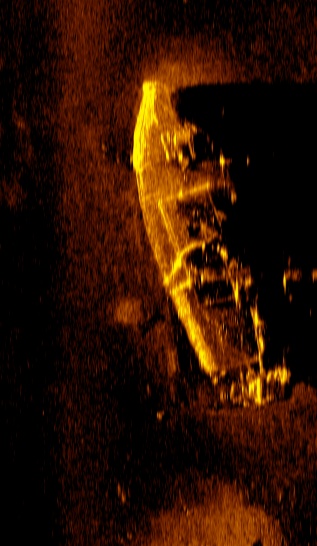

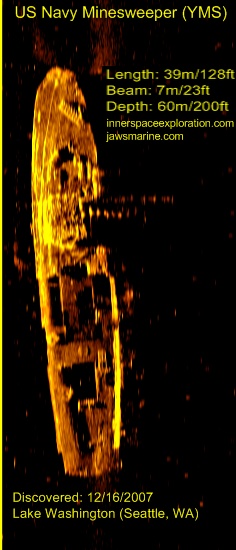

This past Sunday, in a joint effort between JaWS Marine and Innerspace Exploration, we located a previously undocumented Navy Minesweeper in Lake Washington. This ship is 130ft in length, 24ft wide and is sitting in 200ft of water off Sand Point/Magnuson Park.

The YMS designation stands for Yard class Mine Sweeper. These ships were used during WWII for near shore mine sweeping as means to prepare for amphibious based assaults. More detailed history on the YMS located here and here.

Dive and ROV operations have not yet begun on this ship, so we do not yet know which of the 481 YMS ships built during WWII we have located. Based on experience with the relatively well known YMS-359 also located in Lake Washington, as well as other submerged minesweepers, we’re hoping the white designation numbers will still be visible on the bow.

Included below are a few sonar images from our work on Sunday, as well as some YMS 3D modeling images courtesy of Infusion Studio’s 3D.

A few things to look for when comparing our sonar images to the model photos: the narrow, but tall pilot house, fenders on stern deck (these reflect very brightly in the sonar image), opening in hold where ‚Äėspool‚Äô use to sit, opening in hold at engine compartment (meaning engines were removed prior to sinking), forward mount for guns.

More on this one as the story unfolds; I hope to post underwater images here before the end of the year.

I learned more of the history of the MT6, which is sunk in Elliot Bay, from the Puget Sound Maritime Historical Society.

Rather than try and retell it’s life story I capture some quotes from that organizations monthly journal here:

Formally the Tacoma, it was ‚Äúa ferry that took trains across the Columbia River 100 years ago.‚Ä̬† ‚ÄúShe was the reliable workhorse that the Northern Pacific Railway Company needed to complete its transcontinental service from Duluth, Minnesota, to Puget Sound.‚Ä̬† ‚ÄúThe massive railroad ferry became an icon for [the town of] Kalama, her home port.‚Ä̬† ‚ÄúA product of the industrial revolution that crossed the Atlantic, Tacoma brought a mammoth representation of 19th century mechanical engineering to a fledging corner of North America.‚Ä̬†

‚ÄúThe Northern Pacific Railway Company contracted with Harlan and Hollingsworth Company of Wilmington, Delaware, to build an ‚ÄėIron Steam Transfer Boat‚Äô for the staggering price of $400,000.‚Ä̬† ‚ÄúThe vessel was completed in the summer of 1883.‚Ä̬† At the time, she was, ‚Äúthe second largest ferry in the world.‚Ä̬†¬†

‚ÄúFebruary 1884: The ferry package in labeled boxes, arrives in Portland, in 57,179 pieces.‚ÄĚ

‚ÄúOctober 1884: The ferry carries its first freight cars‚ÄĚ

1903: ‚ÄúPresident Theodore Roosevelt‚Äôs tour of the west, which included‚Ķ a whistle stop in Kalama on May 22, undoubtedly entailed ferrying the presidential train across the Columbia River on Tacoma.‚Ä̬†¬†

‚ÄúIn 1908, after 24 years of service‚ÄĚ supporting the booming rail transportation industry, ‚Äúthe iron transfer boat was no longer needed.¬† The railroad bridge across the Columbia River at Vancouver, WA, was completed‚Ķ and the Tacoma made her last run on December 25th.¬†

‚ÄúIn 1909 she was [re]assigned to transport rock to build the North Jetty at the mouth of the Columbia River‚Ä̬†

‚ÄúMilwaukee Railroad purchased the vessel in 1917 and towed her to Puget Sound, where she was stripped down, renamed Barge No. 6, and used to transport railroad cars across the Sound.‚ÄĚ

‚ÄúIn Seattle‚Äôs Elliot Bay, on the morning of January 1st, 1950, the 6000 ton freighter Fairland was trying to avoid a tow of logs.¬† She collided with the Milwaukee Barge No. 6 (formerly Tacoma) that sank in 20 minutes.¬† Her crew of four were rescued by the tug Sandra Foss.¬† There were 19 railcars aboard her ‚Äď of which 15 were loaded with lumber.¬† Six of these broke loose and floated ashore where they could be recovered.¬† They were lifted aboard another rail-barge by cranes from the Foss Company who had the salvage contract.‚Ä̬†¬†

Credit: The Sea Chest.  Journal of the PSMHS.  Dec 2007

Despite truly horrible viz in the lake take, JaWS Diver Scott Boyd was able to get a couple good shots of the Hauler this past weekend.

JS

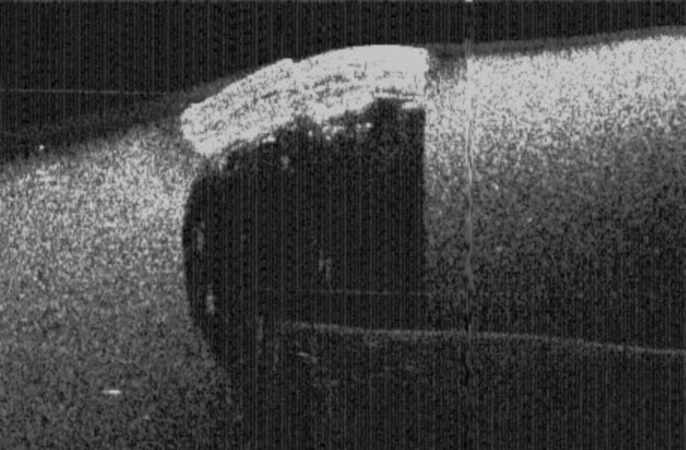

Additional image of the Hauler as recorded by the sonar crew today; great detail in the shadow of this image showing roof line, windows and open bow.

If you look closely at the top down view of the wreck you can see a rectangular opening in the mid ship. I dropped into this hole on the dive mentioned in the first post about the Hauler but I was focused toward the bow.  Divers on the wreck today discovered that entrance leads to a lower room back toward the stern complete with sink and mirror.

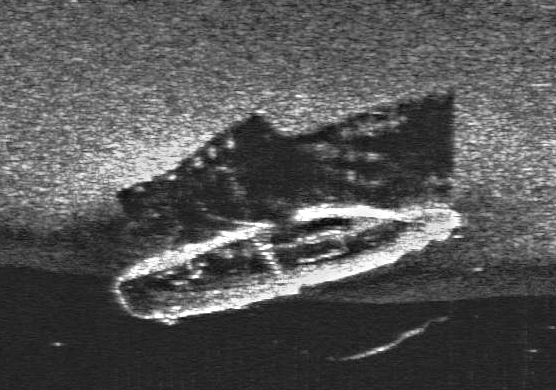

This past Sunday I hit the water with a new sonar crew operating on the lake.¬† Locally they are known as the ‚ÄėNAUI boys‚Äô because of their training background.¬† The short story on them is they are a real solid bunch of guys, good DIR divers and they are using sonar equipment by Burton Electronics.

We focused on an area off Leschi pretty hard, looking for a specific wreck in that general location that we knew had been missing for almost 100 years.

By the end of day Sunday, we had spent about 6 hours on the lake.  It was raining really hard all day, and the wind was blowing some sizeable waves, but in their fully covered/enclosed 34ft boat we stayed pretty comfortable the whole time.  And by the time we left the water we were armed with the following sonar image, showing a shipwreck of about 60ft in length:

The image is somewhat grainy, but if you look at it closely there are a few things you can determine:

– Rounded stern (left side) ‚Äď note roundness of stern in shadow

– Sonar passing through portion of stern ‚Äď usually indicates windows or open deck with overhead structure

– Appears to have square faced cabin structure at the aft end of the ship

– Long open bow

Monday evening we made the first discovery dives on this wreck, which lies in about 120ft of water.

Pre dive I had somewhat convinced myself we had found the Acme.¬† The Acme was a passenger steamer that operated on the lake before the bridges.¬† It burned and sank off Leschi in 1908 and it happened to be 60 feet long ‚Äď and there aren‚Äôt too many unfound 60ft wrecks in Lake Washington.

As it turned out this wreck appears to be an old hauler of some kind.¬† Possibly from the original Foss Launch and Tug Company.¬† I am guessing its era is from the 1920‚Äôs to 1940‚Äôs.¬† It has a round stern with no aft deck, square windows on the top portion of the cabin with additional portholes below.¬† A square cabin face with one door and then a large open deck that has a 4×6 sized opening in the middle and a closed metal hatch near the bow.¬† A wooden craft with large rudder and propeller still in place.

It will take some time to identify this wreck.  I am having trouble even locating a top-side photo of a boat that looks similar to this one.  It reminds me of a container ship shrunk down to 60ft in length.

One interesting note about the dive ‚Äď we saw salmon all over this wreck; and they were aggressive.¬† We rarely see much life at all at the bottom of the lake, so it was unique to come across¬†a half dozen salmon.¬†

Special thanks to the NAUI Boys: Scott, Shaun, Marc, Greg & Ben on this one.  They were instrumental in locating the wreck, and the first divers to see this ship in what has probably been 70 or 80 years.

JS

We conducted dive ops on the last of the three newly discovered targets in Lake Washington today.

Attached is the sonar image for Target1; now identified as the Phoenix.  The Phoenix rests in 200ft of water off Madison Park.  Her length is approx 50ft, width: 14ft, 9-10ft rise

Initially, from a read of the sonar image, I expected Target1 to either be an early century sailboat or, because of the square lines, a PBR type military craft.

In reality this one appears to be a work or fishing boat of some type, built for offshore use.¬† The construction is wooden, but the roof is reinforced with GRP (glass reinforced plastic).¬† There are ‘chain plates’ jutting upward on both sides like sets of metal ribs which look to have supported a small sail.¬†

Guessing the boat was built no earlier than the 40’s, no later than the 60’s (based on general construction), but sank no earlier than the 60’s.¬† The later assumption made due to the presence of the GRP.¬† We also noted there was protection above the forward hatch, used to prevent breaking seas from entering the forecastle, as support for this boat being built for offshore use.¬†¬†¬†

The Phoenix is very well intact, but generally stripped of equipment.  It has a large main cabin, as well as an aft cabin that extends nearly to the stern.  In the sonar photo what looks like what might be the stern of the wreck with a sail crumpled up behind is actually the back of the aft cabin with about 5 feet of semi collapsed stern deck behind.

All the cabin access points still house freely swinging doors with glass and brass hardware.¬† This is not a very common sight for sunken wrecks of Lake Washington.¬† Most of the cabin windows are still intact as well – a few broken, one with the circular break from a rock or baseball.¬† It is somewhat of an eerie feeling to be interacting with a wreck that hasn’t been seen for 45+ years, opening doors that have not moved since they last had natural light shining on them.¬† The first door I opened I half expected some(thing) inside to jump out at us.¬† : )¬†

Inside there is a tarp or sail of some sort which looks like is covering something large, but not wanting to silt out the visibility for the video we were shooting today, decided against disturbing it.¬† Also inside the cabin, not visible unless you swim inside, is an old ‘pot belly’ stove.¬† Quite a nice find.¬†

I hope to have photos of the wreck and some of its artifacts up on the website next week.